What Happened to the Brass Band Music Written during the Civil War

That there was a proliferation of brass bands with all the necessary hardware in mid-nineteenth-century America there is no doubt. But what of the hundreds of thousands of pages of music composed, arranged, published, or otherwise distributed from which the bands learned and played their parts? We regret to say, without unduly disparaging those who provide the present writer with a most worthy excuse for his profession, that paper, the fragile substance to which we commit many valuable records of our civilization, did not often survive the handling of practical musicians. A cinematic anecdote comes to mind. “When a piece of paper gets old, what happens to it?” asks a professorial William Holden in a motion picture sequence filmed on the steps of the Library of Congress. This leading and, under most circumstances, rhetorical question is addressed to a “dumb blonde” played by Judy Holliday. Her querulous response is predictably practical: “You throw it away?”

Here is a brief account of some of the most notable remnants of brass band music in the collections of the Library of Congress Music Division which document that part of our musical past.

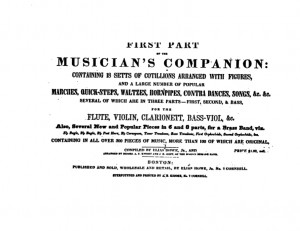

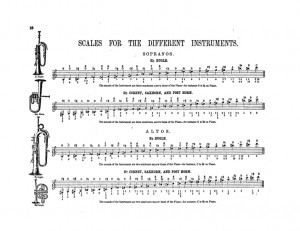

In 1844 Elias Howe published in Boston his First Part of the Musician’s Companion. It contained a number of “new and popular pieces in 6 and 8 parts, for a brass band, viz.: E-flat bugle, B-flat bugle, B-flat post horn, B-flat cornopean, tenor trombone, bass trombone, first orphecleide [sic], second orphecleide, &c.” These are printed in full score with movable type in the oblong format common for collections of sacred and some secular vocal music of the time.

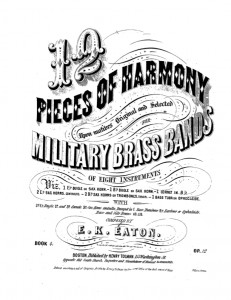

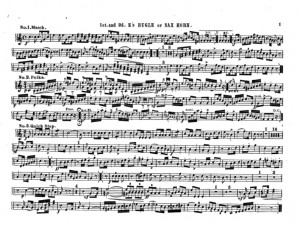

Two years later, E. K. Eaton published, in elegantly engraved parts, Twelve Pieces of Harmony for Military Brass Bands. The instrumentation is larger than Howe’s, calling for “E-flat bugle, 2 B-flat bugles, 1 cornopeon [sic] or post horn, 2 E-flat trumpets, 2 French horns, 2 alto ophecleides [sic], 3 trombones, 2 bass ophecleides, and side drums.” The pieces are rather difficult and demand equally high standards of musicianship from the entire ensemble.

Two years later, E. K. Eaton published, in elegantly engraved parts, Twelve Pieces of Harmony for Military Brass Bands. The instrumentation is larger than Howe’s, calling for “E-flat bugle, 2 B-flat bugles, 1 cornopeon [sic] or post horn, 2 E-flat trumpets, 2 French horns, 2 alto ophecleides [sic], 3 trombones, 2 bass ophecleides, and side drums.” The pieces are rather difficult and demand equally high standards of musicianship from the entire ensemble.

By 1849, Allen Dodworth was instructing readers of the New York music journal Message Bird on the formation of brass bands. On August 1 of that year, in the first of several installments, he writes:

“What, in our opinion, would make the best arrangement for a Band of ten, would be as follows: Two E-flat Trebles, Two B-flat Altos, Two E-flat Tenores, One B-flat Baritone, One A[-flat] or B-flat Bass, Two E-flat Contra Bass. If more are required, add two Trumpets; then two Post-horns; then two Trombones; Drums, Cymbals, &c. Many different kinds of instruments are used to take the parts here mentioned, but most of the Bands of the present day give preference to what is called the Saxhorn, which is made in all the different keys mentioned above.”

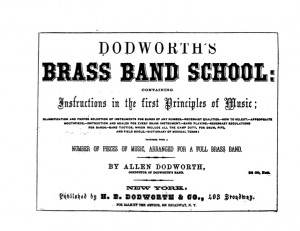

In 1853 Dodworth published his Brass Band School, complete with scores for a number of pieces calling for the same instrumentation advocated in the Message Bird. Although he takes into account the variety of brasswinds available, including the keyed bugles and ophicleides, it is the saxhorns that get the highest recommendation. “I have always, in my own mind,” he writes, “classed Trumpets, Post Horns, Trombones and French Horns, as supernumeraries; for, since the introduction of [keyed] Bugles, Cornets, Ebor Cornos and Sax Horns, they are no longer depended on for the principal parts.” In forming a band of up to fourteen players, he advises: “Let nothing but Sax Horns, Ebor Cornos and Cornets, or instruments of like character be used, that is, valve instruments of large calibre.”

Here, he also mentions the special invention of the over-the-shoulder style horn. “In selecting the instruments, attention should be paid to the use intended; if for military purposes only, those with bells behind, over the shoulder, are preferable, as they throw all the tone to those who are marching to it, but for any other purpose are not so good. These were first introduced by the Dodworth family in the year 1838.” The application of this style probably was restricted to the trombones at first, but its popularity continued through the 1880s, for we find such instruments advertised in dealers’ catalogs, along with the bell upright and bell front models, as late as 1888.

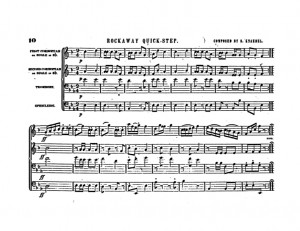

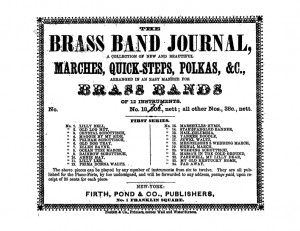

In 1853 Firth, Pond and Company of New York began the publication of its Brass Band Journal, probably the first American publication of saxhorn pieces. The longevity of these attractive compositions and arrangements by G. W. E. Friederich is attested to by the fact that they were still being offered for sale in the 1870s.

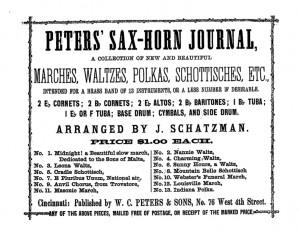

A similar publication appeared in Cincinnati in 1859. It consisted, for the most part, of popular dances and quicksteps arranged from piano pieces for a band of from six to twelve players and was published by W. C. Peters & Sons as Peters’ Sax-Horn Journal.

When the Civil War broke out, many of the bands were using this music but with the introduction of new music much of the bands used tailor made arrangements to suit their ensembles.

Much of this music has been available from online sources like the Library of Congress. JV MUSIC has taken this lost brass band music, organized it into files and made high resolution facsimiles of this material. They are available through our store. The music is in PDF format and downloads upon payment. Careful work has been done to retouch and clean up the original music. Many of our scans come directly from the ORIGINAL material, not copies of copies. We will be adding many selections from the various books mentioned above. If you are looking for a particular selection please drop us a line at info@jvmusic.net

If you enjoyed this article, you may be interested in our article on Brass Bands of the Civil War.

Enjoy!